Electronic circuits are found in almost everything from smartphones to spacecraft and are useful in a variety of computational problems from simple addition to determining the trajectories of interplanetary satellites. At Caltech, a group of researchers led by Assistant Professor of Bioengineering Lulu Qian is working to create circuits using not the usual silicon transistors but strands of DNA.

The Qian group has made the technology of DNA circuits accessible to even novice researchers–including undergraduate students–using a software tool they developed called the Seesaw Compiler. Now, they have experimentally demonstrated that the tool can be used to quickly design DNA circuits that can then be built out of cheap “unpurified” DNA strands, following a systematic wet-lab procedure devised by Qian and colleagues.

A paper describing the work appears in the February 23 issue of Nature Communications.

Although DNA is best known as the molecule that encodes the genetic information of living things, they are also useful chemical building blocks. This is because the smaller molecules that make up a strand of DNA, called nucleotides, bind together only with very specific rules–an A nucleotide binds to a T, and a C nucleotide binds to a G. A strand of DNA is a sequence of nucleotides and can become a double strand if it binds with a sequence of complementary nucleotides.

DNA circuits are good at collecting information within a biochemical environment, processing the information locally and controlling the behavior of individual molecules. Circuits built out of DNA strands instead of silicon transistors can be used in completely different ways than electronic circuits. “A DNA circuit could add ‘smarts’ to chemicals, medicines, or materials by making their functions responsive to the changes in their environments,” Qian says. “Importantly, these adaptive functions can be programmed by humans.”

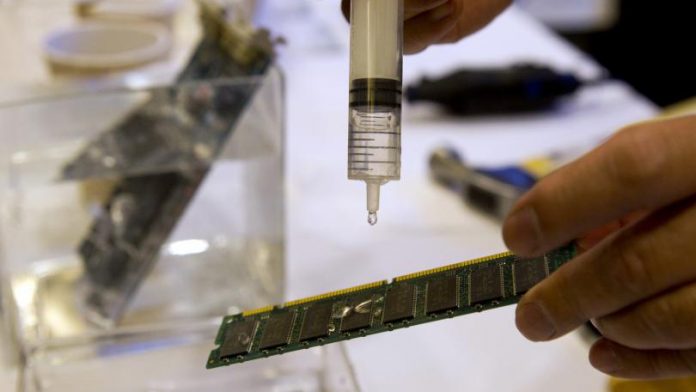

To build a DNA circuit that can, for example, compute the square root of a number between 0 and 16, researchers first have to carefully design a mixture of single and partially double-stranded DNA that can chemically recognize a set of DNA strands whose concentrations represent the value of the original number. Mixing these together triggers a cascade of zipping and unzipping reactions, each reaction releasing a specific DNA strand upon binding. Once the reactions are complete, the identities of the resulting DNA strands reveal the answer to the problem.

With the Seesaw Compiler, a researcher could tell a computer the desired function to be calculated and the computer would design the DNA sequences and mixtures needed. However, it was not clear how well these automatically designed DNA sequences and mixtures would work for building DNA circuits with new functions; for example, computing the rules that govern how a cell evolves by sensing neighboring cells.

“Constructing a circuit made of DNA has thus far been difficult for those who are not in this research area, because every circuit with a new function requires DNA strands with new sequences and there are no off-the-shelf DNA circuit components that can be purchased,” says Chris Thachuk, senior postdoctoral scholar in computing and mathematical sciences and second author on the paper. “Our circuit-design software is a step toward enabling researchers to just type in what they want to do or compute and having the software figure out all the DNA strands needed to perform the computation, together with simulations to predict the DNA circuit’s behavior in a test tube. Even though these DNA strands are still not off-the-shelf products, we have now shown that they do work well for new circuits with user-designed functions.”